Designing a collaborative governance model for Canadian mission oriented innovation

Photo by Prometheus 🔥 on Unsplash Image of mushrooms growing on a tree in a forest.

At the beginning of June I found myself in Halifax, Nova Scotia for the third Canadian Forum on Social Innovation. Since first calling this Forum together, Sandra Lapointe and her team at The Collaborative have been working on deepening the connections across academia and “pracademia”, public policy, nonprofits, philanthropy and practice and 2025 felt like a bit of a watershed. Thanks to its partnerships with Social Innovation Canada and the Canadian Science Policy Centre, there was a strong mix of participants and perspectives. As the Forum heads to Calgary next year, I’m sure the diversity of participants will continue to grow.

The focus for this year’s gathering was two-fold: Building Capacity for Ecosystem Connectivity and Intelligence for the Implementation of Mission-Oriented Innovation Policy.

The mission-oriented policy conversation was held as jurisdictions across the world attempt to coordinate cross-sectoral efforts to address complex social and ecological challenges. Tim Draimin and I recently wrote about various EU and UK missions and other applied approaches in a piece prepared for The Collaborative and available here.

On Day 4 of the Forum, Roots & Rivers Consulting sponsored a panel on Mission-based innovation, hosted by.Andrea Nemtin, CEO of SI Canada; and then Annelies Tjebbes, Hayley Rutherford and I ran a workshop on Mechanisms for Cross-Scale Collaboration & Alignment. Across that afternoon, all workshops dove more deeply into the kinds of relationships, structures and systems we might create or uplift at a community level to support successful Mission-Based Approaches in Canada.

Often described similarly to the SDGs or the Millennium Development Goals, missions set forth a new narrative and set of infrastructures first advanced by UK economist, Mariana Mazzucato. The UK’s Labour Government successfully campaigned on a mission narrative in last year’s elections and now we watch as they attempt to deploy the strategy.

For some at the Forum on Social Innovation the concept was completely new and so I’ll share the definition put forward by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD):

“a mission refers to a well-defined overarching policy objective to tackle a societal challenge within a defined timeframe. Missions are typically bold and ambitious, involve a large range of stakeholders across sectors and require significant innovation and coordination. They are also characterized by a long-term vision and transformative ambition…”

With this definition in mind, Forum participants were convened to think through how we build capacity for the connectivity required to host missions and what we need to know to implement them. Even if Canada decides not to go the way of missions as defined above, certainly the kind of collaborative infrastructure it calls for is necessary to address complex challenges and thus, the exercise seemed more than useful.

Prior to the resignation of former Prime Minister Trudeau in Canada earlier this year, the political headwinds suggested a change in government. As the conversation around missions was picking up steam, it was unknown whether a potential Conservative government would entertain the mission approach. As I prepared to visit my family in Australia in March, Future of Labs colleague and deep systems thinker, Sam Rye and I plotted a gathering of university staff and academics in Melbourne to discuss a university’s role in leading missions when/if a government won’t. Several universities in Europe have written about such an option, so we thought it worth exploring.

Monash University had recently published a report on mission-based innovation research for complex challenges, highlighting 10 case studies from their work to impact systems change. While they retrospectively applied the mission terminology, they examined the characteristics of the cases using a mission lens to assess whether their approach to collaborative partnership projects qualified.

I went into the Monash University meeting wanting to understand how the university holds space for collaborative partnership and what successes and challenges they have experienced as they go about their project work. I was impressed to learn that the university’s senior leadership is involved in all projects with a Research Missions team in the Office of the Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Research and Enterprise). Where I have heard of barriers in Canada to senior leadership’s embrace of cross-faculty and transdisciplinary collaboration, this is not the case at Monash.

Working across challenge areas as diverse as net-zero development projects, mosquito-born disease eradication and hyper-local community-led disaster response strategies, the scope and scale of the projects was compelling. It was also interesting to learn how cross-sectoral the teams were in execution. There was clear and necessary university and public sector collaboration and partnerships with various private sector actors as well.

The research capacities and resources of the university were highly useful to all projects. The institution also played a role in shifting incentives and structural boundaries to enable the participation of academics, staff and students alike.

Unfortunately, meeting participants spoke of fewer collaborations with the nonprofit and charitable sector, which felt incongruous to the outcomes being sought. To quote one of the staff, “There just isn’t a process for a nonprofit to bring in a research question to us.” This hasn’t stopped collaboration with the nonprofit community altogether but it’s a limiting factor to be sure.

In Canada, there are existing Community-University Partnership offices that could help advance a mission agenda. There are also robust community-college relationships that could be activated to enable experimentation in place-based mission innovation activities.

When I asked the Monash participants whether or not a mission’s governance could be held outside the institution to allow for different power and equity arrangements, they expressed an openness to the idea but qualified that the university itself may deem it too risky.

I thought a lot about this as I travelled back to Canada and wrote up my reflection for The Collaborative. How do we de-risk equitable collaboration? Is that even the right question? If there is risk involved with engaging authentically and equitably around a complex challenge - that invariably most impacts people or ecologies at a community level. So, whose risk is considered too valuable to put on the line?

At the Halifax Forum, Matthew Mendelsohn, CEO of Social Capital Partners, spoke eloquently and passionately about the risk universities take in not engaging deeply with communities. Citing the US Government’s current crackdown on post-secondary education, he says these institutions are made more vulnerable to attack when they appear disconnected from the communities around them. No one will fight for something they don’t feel has their interests at heart. To avoid this fate, universities might examine their relationships and processes and work even more actively to open themselves up to both risk and reward.

Moving away from the university as mission-host, where else might this collaborative governance sit? Mazzucato would say at the federal government level. Now that Canada has returned the Liberals to office, perhaps this is a more likely possibility. In Halifax, the final day’s deliberations considered if Prime Minister Carney’s recent Mandate Letter was a 7-mission call to action.

Certainly, the Federal government should be at the table as champion for missions, providing enabling legislation, funding, incentives and public service capabilities. Some might argue that they demonstrated mission-like capability during the pandemic - rapidly passing legislation, removing barriers, distributing funds to those most vulnerable, communicating the all-in-this-together narrative that helped keep the virus from spreading further and more seriously than it did. Could they harness this learning and apply it to their own stated mandate - mobilizing all sectors and igniting the imaginations of community to get on board? Maybe.

Given what we know of the agility of public sector systems and the current deployment and direction of innovation funding ie. through private sector and university research and development (R&D) programs, how will communities, nonprofits and community-engaged institutions like colleges be engaged? Recalling again the innovation generated during the pandemic: while the federal government initiated considerable activity, legions of volunteers and community agencies mobilized independently to coordinate food, healthcare, transportation, communication, translation and more in neighbourhoods, small towns, across faith, immigrant, and unhoused communities. It was a masterclass in hyper-local innovation and this capacity should not be forgotten in the design of a mission strategy.

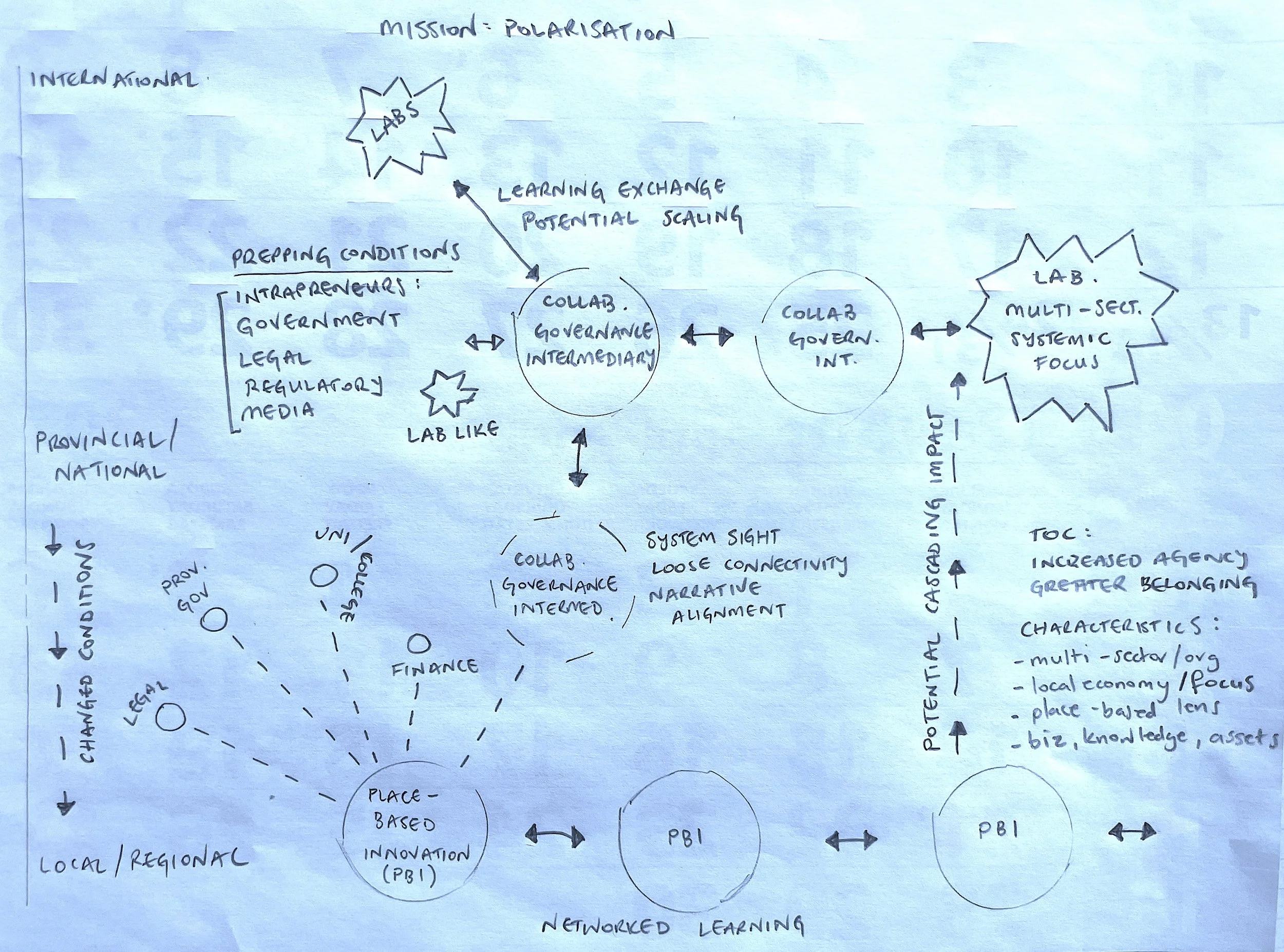

Image: Super drafty sketch of collaborative innovation infrastructure possibilities

Not ignoring the strengths and necessary resources of the private and philanthropic sectors, and with all the above in mind, what might it mean to call together a network of intermediary teams and design a collaborative governance infrastructure that can guide missions and the involvement of all institutional actors and communities? These teams would have strong lab-like mind- and skill sets to act as orchestrators (collaborative governance intermediaries) across and between projects.

Borrowing from Tim Draimin’s report again, “the emerging knowledge field of system change acknowledges the multifaceted nature of that change and the need for what some analysts call system orchestrators. In the context of social innovation and systemic change, a system orchestrator is an individual or organization that works to enable, coordinate, and accelerate large-scale societal transformations. They aim to address complex social or environmental challenges by aligning various stakeholders, resources, and interventions to create meaningful, sustainable change.”

The role of orchestrator needs an experimental mindset; the agility and ability to change course and hold others through that change. From a social innovation perspective, they also need an orientation to relationality and attention to equity, justice and inclusion is also critical.

In the Mission Playbook developed by the Danish Design Centre, they write: Missions call for a structure that balances stability and agility – predictability and unpredictability. That means creating a governance structure for the mission work that leaves room for changing the project portfolio and the actor landscape as the mission progresses.

Similarly writing about governance in 2024, Ingrid Burkett of the Good Shift in Australia outlined:

“Though some may consider it the ‘boring’ part of transformational work, our observation is that often governance is the element that ultimately enables or undoes collective action initiatives. In complex change contexts, the governance of these entities needs to be acting as both the glue and the compass guiding the collective action.”

Guided by this thought leadership, it feels possible to imagine that a federal government, philanthropy or university could call a mission and that the orchestrator for the collaboration between all those actors and the community, could be a set of agile, experimental, risk-happy and relational intermediaries with aligned principles, all acting in service to the whole.

It seems ideal and more realistic that much of the innovation activity required to meet the mission, not be centrally controlled. In the spirit of distributed innovation, much of this activity could follow “minimum mission specifications;” think a shared narrative and principles, to be tracked by the intermediaries.

Within the context of group dynamics, our constellation metaphor is a way to recognize that there are many stars in the sky and it is the power to cluster, to bring order and to assign meaning to these groups that provide a framework for organizing and action.

I’ve thought a lot about Tonya Surman’s work on the Constellation Model in writing up this piece. “The Constellation model is a way to bring together multiple groups or sectors to work toward a joint outcome…; it also recognizes energy and respects how this energy flows in a group. It is an attempt to develop a framework to understand and support the tensions that exist when several groups come together.” We need this kind of attention and intention with the mission governance framework. A social innovation mindset will help serve this intention given the various combinations and distributed activities at play.

As global systems feel further and further away from the lived experience of people at the local level, and money circulates among fewer and fewer hands, place-based innovation is coming to the fore. People want to feel some sense of control over where they are, how they are governed and what projects feel best for them. As during the pandemic, this kind of innovative activity should be championed by the mission host and not tightly controlled.

At the same time, there is a need for innovation in our mainstream systems - policy, economic, legal and so on - to prepare conditions for solutions generated throughout the mission to be introduced. As colleagues at UpSocial in Spain have found, it’s often not the generation of new solutions that’s required, but identifying what works and creating an environment in which those solutions can be introduced.

And finally there will be a need to call more robust multi-sectoral innovation projects together at a broader systems level, to identify leverage points, prototype and scale interventions where maximum impact is most possible. Think of the combinations of assets, skillsets and agency to tackle climate change, global insecurity, AI governance, polarization. These challenges need to be addressed at national and international scales and with particular sets of intermediaries.

Of course, all of this distributed activity will need to be financed. This kind of multisolving, as Sam Rye puts it, calls for considerable investment of various types. Sam hosted a webinar in early March on a number of these components and I agree with his reflection that “areas of systemic investing, community finance, and place-based capital are mutually reinforcing.” Add to these government and private investment at scale and we get closer to a starting point. Take a look at the webinar to learn more and also check out a more recent event on Systemic Investing hosted by Impact United Academy, TwinRiver Capital, Dark Matter Labs, and Ontario Trillium Foundation to learn about Canada’s systemic investing potential.

For now, I’m interested in the design of the orchestration platform: networked intermediary innovation teams informed by lab mindsets and skills sets connected to work happening at all systems levels. Whatever the form, this governance structure should accelerate our capacity to realize transformation. I’ve been super happy thinking through the possibilities with Sam and Ione Ardaiz of Arantzazulab over the past several months, brought together by the fabulous Future of Labs convening.

Now I would love to co-design it and test it out!

Postscript: For an excellent follow up on Collaborative Leadership and Governance, read this Tamarack Institute series.