Remixing democracy and social innovation

At Democracy R&D: Where Tech Meets Talk: Can Deliberation and Technology Work Together? Panelists: Liz Barry, Dr. Angela Jain, Aviv Ovadya, Taylor Owen, and Kris Rose Moderated by: Peter MacLeod

While media cycles continue to churn out almost perpetual bad news, it can be hard to drum up the energy to keep your social change efforts going. Make no mistake, there is a lot of bad news out in the world that shouldn’t be ignored, but thankfully there are many people also tackling the great challenges of today with determined intensity. Many of these people also help direct where change efforts can have a big impact.

In Mariana Mazzucato’s September article for IMF’s Finance and Development Magazine titled Policy with a Purpose, she outlines why we’ve been unable to address the climate crisis, writing:

“The crisis is not an accident but the direct result of how we have designed our economies—particularly public and private institutions and their relationships;” and then helpfully offers: “This means that we have agency—the power to redesign them to put planet and people first.”

Mazzucato’s point on agency hits home strongly with me. The will and capacity to do something is so important; especially when it feels like the polycrisis renders us impotent and our democracies suffer from direct assault and a lack of engagement.

I’ve been writing on, advocating for and working with social innovation lab processes for the last several years, with a particular affinity to UpSocial, developed by Miquel de Paladella. These models offer stakeholders a direct opportunity to exercise their agency.

For those new to these approaches: “Social innovation Labs hold space for diverse change-makers to sense-make, generate, develop and test a portfolio of promising solutions to address complex societal challenges in a way that is collaborative, experimental, iterative, and systemic.” (Future of Labs Primer 2024)

Labs create a framework to work on a complex problem - like one of the myriad challenges associated with climate change. They can be very powerful contributors to change efforts but they are tricky to gain support for as they are generally long, expensive and can’t guarantee success. See this clarion comic by colleagues Alex Ryan and Keren Perla produced following the Future of Labs this year, to better understand the barriers to support.

The value proposition challenge: From the Unregulators series produced by Alex Ryan and Karen Perla. Illustrated by Alex Magnin.

Jokes aside, many of us left the Future of Labs committed to working on their value proposition. The outcomes made possible by these lab processes can be transformative. And it’s their broader application that’s needed in this time.

This past month I attended my first Democracy R&D Conference in Vancouver, BC. Hosted by the crack team at MASS LBP and the New Democracy Foundation and attended by practitioners from around the world, this was my first exposure to a way of facilitating democratic processes that taps into the agency of the public at large - and to my mind - offers a promising addition to our social labs approach and value proposition.

Before I get into the connection, I want to first express my excitement over finding this democracy innovation community, courtesy of a tip from Ione Ardaiz Osacar from Arantzazulab. Although I knew of the work of MASS LBP, I didn’t fully grasp there was a global cohort working on strengthening our democratic processes.

I’m sure I’m not alone in worrying about how democracy is under threat, so learning of this broad effort was inspiring in itself. Like social labs, they work against the assumption that people can’t possibly have an impact on complex social and environmental challenges. In fact, I think they demonstrate even more powerfully than labs that people want to contribute to decision making on matters of governance and policy, and many practitioners have been facilitating their access for years.

While the suite of democracy innovation efforts is broad, one of the main vehicles is the hosting and facilitation of citizen assemblies. Note: the use of the term citizen is not exclusively applied to formal citizenship, but to any person living in a country or region with an address or location where they can be reached.

A citizen assembly is a broadly representative group of around 50 – 150 members of the public who are chosen, by lottery, to discuss and make recommendations on a specific policy question or set of questions as part of the policy-making process. (Institute for Government)

Just as in the use of Labs, there are certain conditions or types of deliberation where these assemblies are most effectively deployed:

Assemblies have been very effective in deliberating matters of ethics eg. abortion rights or end-of-life legislation.

They are also very good at working through complex problems that involve trade-offs - where the thoughtful presentation of research and information can be worked through and discussed with the participants, and a set of recommendations put forward.

Lastly, they are not usually struck on short term matters, but on issues pertinent to long term policy ie. beyond the election cycle.

Part of what makes the approach so compelling is the random selection process used to find the assembly members. In many ways it mirrors the practice of jury selection, but with less sway on the part of lawyers and prosecutors in the final composition. Whether at a city, region or national level, letters are mailed out via the postal service (or connection made through canvas) to, oftentimes, thousands of people. The recipients are given information about the reason for the assembly eg. to consider electoral reform options, and then asked to opt into the next round of vetting. From there, the convening team cross-reference demographics for a representative sample ie. age, ethnicity, gender, occupation etc. Then a final group is selected. (See the Sortition Foundation for more on the process.)

It’s not nothing to be selected. The obligation often involves 40+ compensated hours of in-person time over weeks or months. From those gathered at the Democracy R&D conference, experience suggests that nominees are both excited and proud to be selected. Prior to the conference in Vancouver, British Columbia celebrated the first Citizens Assembly held 20 years ago on electoral reform. Those currently engaged in assemblies or who took part 20 years ago, shared stories about how transformational the experience was for them.

However, just like with Labs, the outcomes of these processes are mixed. Some advocates say the experience is regarded as an outcome in itself - people value contributing to policy recommendations, the exposure to different worldviews shatters assumptions, and the agency exercised is valuable. In some cases, like those in Ireland, citizens assemblies are commonplace and have contributed to the passage of legislation around abortion rights and constitutional reform. France also used a citizen assembly in the development of laws relating to assisted suicide and euthanasia.

Yet, the development of recommendations by consensus using the citizen assembly doesn’t always result in the changes they desire. While the first BC Citizens Assembly celebrated last fortnight developed a recommendation for electoral reform, the referendum that followed it was unsuccessful. Nothing is a given, but the pursuit and exercise is still worthwhile. Politicians who accept the recommendations are, at the very least, better informed as to public sentiment.

As I wrote earlier, in attending the conference, I was interested in learning more about how these democratic processes may add value to lab approaches and our value proposition. Without a doubt I feel they have multiple contributions to make. While many lab processes do a great job of engaging a diverse set of stakeholders around a common challenge, the random selection of a representative group of people could help build even greater legitimacy over the final outcomes. They also foster a sense of trust and relevance in the outcome which could strengthen a case for support.

While democracy innovation is primarily focused on matters of policy and governance, we know labs don’t always result in a policy reform or law. They may require the engagement of markets or the broader culture to see a solution scale. Despite this difference, were you to engage a similar process at points in the lab: designing the brief, prototyping and before pilot or adoption, an assembly could help advise on the best initiative to introduce.

In many labs, stakeholder composition starts with an intentional preference to engage and centre of people who are most impacted by a challenge area eg. issues of homelessness, under/unemployment. This is an important distinction and necessary to solution design. What could a blend of random selection and this deliberate centering look like?

These are musings at this stage but I feel there’s something to work with here. Funders - whether they be government, philanthropic or investors - are looking to generate the greatest impact for their commitments. And while the experimental process of labs helps work through ideation, research, testing and validation, an additional step to gather relevance, legitimacy and trust, could really give the final selection a boost.

Maybe I’ve got the contribution mix wrong or in the wrong place. I’d love to work on it with creative folks similarly motivated. Look at how the two general practices stack up.

Mosaic Lab Process

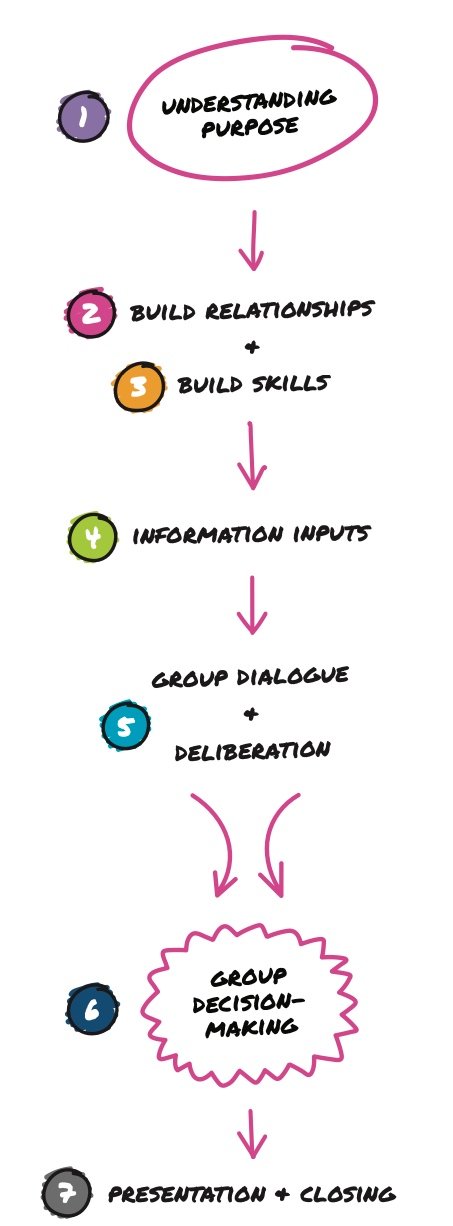

The seven steps outlined here are experienced by the participants in a democracy deliberation process.

Innovation Spiral developed by Nesta. It has informed many lab processes.

Of course it will cost more to integrate the two, but considering the weight of the challenges confronting us all, this investment is peanuts.

Hurricane Helene, which just ripped through the south east of the United States has caused an estimated $100B+ of damage (and counting), which doesn’t account for the tragic loss of life. Addressing the climate change challenge - as Mazzucato suggests - will require finance flows of at least $5.4 trillion a year by 2030 to stave off the worst effects of a hotter planet. The climate challenge is only one of many complex issues we need to reckon with as a global community, so committing even 1% of that price tag towards processes that support solution finding and design, as well as open up the decision-making behind that investment to more people, seems like a small price to pay.

If this combination of innovation processes sound interesting to you, get in touch and let’s design together.

3 bonus takeaways from Democracy R&D

Democracy R&D Keynote: Indigenous Perspectives on Collaborative Governance and Deliberation with Niigaan Sinclair. In brief, for the origins of democracy, look to Indigenous Peoples.

For clear and compelling guides and training for democratic innovation, check out:

Futures fun and insight from Stuart Candy - follow him on Medium.